Monthly

October 2007

BY GREG BREINING

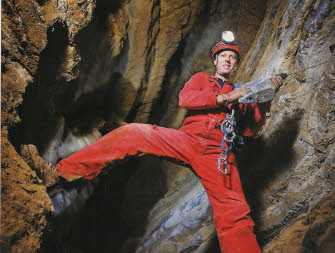

Is bad-boy caver

John Ackerman saving Minnesota caves—or destroying them?

JOHN ACKERMAN WAS EXPLORING a dead-end passage

of an old commercial cave in southeastern Minnesota when he came to

a narrow crevice through which a terrific wind was howling.

For most hobby cavers, that would have been the end: They would have conceded defeat and looked for larger passages elsewhere in the cave. But not Ackerman. Instead of giving up, he bought the property and, in 1989, laid explosives around the edge of the slot. Successive blasts during the next several months allowed him to remove enough rock that he could wriggle through. What he discovered astounded him—a network of “walk-though” passages and enormous rooms, an underground labyrinth that would eventually stretch 5 miles. What thrilled Ackerman most is that he was the first to lay eyes on the place.

|

| “That was a tremendous discovery.” |

Ackerman, it’s safe to say, has discovered more caverns than any other caver in Minnesota. The reason is attitude. Spelunking is often a passive activity. Usually, a passage happens to reveal itself at the surface through the vagaries of geology and erosion, and people explore it. But Ackerman goes out in search of caves. And unlike most other cavers, he has the financial resources to access caverns that others can’t touch. If a heap of rubble or a wall of rock happens to stand in his way, he simply brings in the heavy equipment, or shaves off slabs of rock with high explosives.

Ackerman is building nothing less than a cave empire, buying and cutting entrances into caves he has discovered, and roughly doubling the number of caverns open to local spelunkers. In the process, he has outmaneuvered many other cave owners, including the State of Minnesota, building entrances to caves they once thought they controlled.

Such behavior has earned him some appreciative friends. “What John has accomplished is to make available to scientists, cavers, and the general public an enormous resource that wasn’t there before,” says Calvin Alexander, a University of Minnesota geology professor and hydrogeologist. Joe Terwilliger, president of the Minnesota Speleological Survey, a local caving club, concurs: “Everybody in the club respects him for being as passionate as he is to discover new caves and make them accessible.”

But Ackerman’s forceful methods have also earned him harsh criticism from caving purists. “He is controversial,” says Ron Spong, who founded the Minnesota Speleological Survey 45 years ago. “He can be brash. He speaks his mind. He’s loved and hated at the same time.”

AS A TEENAGER, Ackerman explored

the artificial caverns mined from the Mississippi River bluff (“The St.

Paul caves were cool because we could ride our motorcycles through them,”

he says). It wasn’t until the late 1980s, however, that he became an avid

spelunker. Among the areas he explored was Spring Valley Cavern, a cave

in southeastern Minnesota that was first discovered in 1966. Run briefly

as a commercial enterprise, Spring Valley eventually went bust. In the

late 1980s, though, the farmer who owned the entrance to the cave said

he was interested in selling some of his land. Ackerman, who owns a successful

high-end furniture repair and restoration business, decided to buy 117

acres.

In Minnesota, property owners also own what’s below their land and to

clamber through a cave without permission is considered trespassing, so

Ackerman also negotiated with the landowner to buy the access rights to

any caverns that might underlie the remaining acreage. Thus began the

cave farm that Ackerman dubbed the Minnesota Cave Preserve.

Ackerman’s cave farm, like much of the karst country, is situated amid rolling farmland, pocked by copses of hardwoods that farmers can’t clear or plow because sinkholes (as many as 15,000 in Minnesota alone) lie beneath the surface. By digging into the sinkholes with his “Cave Finder”—a modified backhoe—Ackerman has discovered, at latest count, 42 caves of various lengths that he has opened to spelunkers, local nature groups, and scientists at the University of Minnesota.

On the day I visited the preserve, Ackerman led me down a path to an artificial limestone structure that was artfully hidden beneath the brow of a wooded hill. The building, sheltering the original entrance to the cave, provides a staging area and lockers for cavers and scientists working in the cavern, and cost Ackerman about $200,000 to construct. Dressed in coveralls, boots, gloves, and helmets with LED headlamps, we climbed down a short flight of concrete stairs to the opening of the cavern—the section where a previous landowner had hauled out dirt and gravel to improve access for commercial tours. Within about a half-hour, we squeezed through the slot Ackerman had long ago widened with explosives and entered a tight zigzagging passageway.

Ackerman sped ahead of me,

disappearing down the crooked slot of rock. The more I hurried to keep

up, the more trouble I had wiggling though the narrow crack. Panic gripped

my chest as I felt a wave of nausea. I wanted to thrash my arms and run,

but I was pinned between the rock walls. Ackerman, somewhere ahead, tried

to reassure me. “There’s some crawling and some tight stuff, and after

that, it’s open,” he said. “Out of the entire trip, this is probably the

tightest part.”

I tried to relax, and began to notice stalactites, stalagmites, and ribbons

of flowstone. As we explored, Ackerman pointed out flowstone formations,

from delicate “soda straws” bristling from the ceiling to the massive

Leaning Tower, the largest single “column” known in any Minnesota cave.

He cautioned me to walk in the center of the passages and to touch the

rock as little as possible. (In fact, he won’t allow visitors in what

he calls “pristine” sections, where delicate features are especially abundant.)

We straddled and then waded through a rushing stream with several small

waterfalls. Finally, after squirming on our bellies though a foot-high

gap for 100 yards, we came to the Colossal Room. More than 40 feet high,

35 feet wide, and 75 feet long, it was filled with the sound of flowing

water. “This is it,” said Ackerman, rising to his feet and scanning the

reaches of the chamber with his headlight. “This is why you go caving.”

WHEN HE BEGAN CAVING, Ackerman enjoyed exploring Mystery Cave in southeastern Minnesota. But when the Department of Natural Resources bought the cave in 1988 to add it to Forestville State Park, it locked out the cavers. “I think it was an issue of total control,” says Ackerman. “Remember, everybody was new. No one had owned a cave before.” After intense negotiations, the state opened the cave again to occasional exploration, but the dustup foreshadowed Ackerman’s later disputes with various officials over access. The first involved Coldwater Cave in northeastern Iowa. With more than 17 miles of passages, it is one of the preeminent caverns in the Midwest. Divers probing an underwater passage discovered Coldwater in 1967, and state officials drilled an easier and safer entrance, hoping to develop a commercial cave. But when further money for the project never materialized, Iowa officials handed the access rights back to the landowners, who administered entry criteria that many cavers felt were overly strict and arbitrary. A small clique of cavers won the confidence of the landowners, says the U of M’s Alexander, who still conducts research there. But others seeking entry were shut out. In 1995, Ackerman—armed with a diagram of Coldwater—bought 5 acres adjoining the disputed property and the underground rights to 200 more. He hired drillers to bore a shaft 30-inches across and 188 feet straight down into his portion of the cave. The owners of the original entrance, who in one fell swoop had lost their monopoly on access, were incensed.

Ackerman would employ a similar

tactic four years later, when the owners of Goliath Cave in southeastern

Minnesota sold their land to the state to be designated as the Cherry

Grove Blind Valley Scientific and Natural Area. (A blind valley is a stream

that disappears into a cave.) The DNR promptly closed the cave, ostensibly

to protect the cave’s formations. “We made it very clear we weren’t going

to be giving out any research permits until we had completed an inventory,”

says Bob Djupstrom, then head of the state’s Scientific and Natural Area

program. After unfruitful discussions with the DNR, Ackerman talked to

the adjoining landowner, who agreed to sell him 2 acres and caving rights

to another 360 acres. Then he sunk a new access shaft—directly across

the road from the state’s property. The DNR, says Ackerman, “did back

flips.” Today, a sign sits outside Ackerman’s access point: “Goliath Cave

Site. David’s Entrance.”

The confrontational style tends to obscure Ackerman’s motivation, says

Alexander. “I’ve been poking around in holes in the ground for 40 years

now,” he says. “I always thought the phrase ‘a rich caver’ was an oxymoron.

But John is one. I think a significant component in the problems a lot

of people have with him is envy. He has the resources to do a lot of things

that other people can’t do. The other thing is, he is a hard-driving explorer.

He wants to see things people have never seen before…. There aren’t many

places left on earth where you can see something for the very first time.”

But high explosives and a backhoe?

A caving code is “a nebulous thing” over which cavers disagree, says the

Speleological Survey’s Spong, a long-time spelunker. “Purists” might even

refuse to dig out mud and dirt blocking their way. But most cavers would

do at least that much. And what is the difference, philosophically speaking,

between shoveling dirt and hammering away at an obstruction? If hand tools

are okay, why not a power drill, or the use of a small charge of explosives

to break off a slab of rock? “You’re already making the first jump toward

changing what’s there,” says Spong. “I myself have used explosives.”

Indeed, what is the virtue of keeping a cave pristine and unseen? It’s not as if caves, unlike wilderness areas or wetlands, are in short supply. There are hundreds or thousands underlying the Midwestern karst. Only a fraction of those are open to the public, however.

Late one summer day, Ackerman and I drove to Tyson Spring Cave in Fillmore County. Cavers have known about parts of Tyson Spring for more than a century, but it wasn’t until 1985 that divers were able to swim through two underwater passages that had blocked further exploration. Ackerman was one of those early surveyors, and after purchasing rights to the cave, he—once again—punched through a new entrance. After descending more than a hundred steps into blackness and cold, we alighted at the edge of a tumbling, swift, burbling stream. We clambered over boulders and rapids and waded through pools to our waist, marveling at multi-colored fins and ribbons and entire walls of flowstone. A quarter-mile into the cave, we came to a big chamber and sat down to take in the scene.

As the Minnesota Cave Preserve continues to grow, Ackerman wonders about his legacy: “You build up all of these major caves, but what’s going to happen when I’m gone? Is that next steward going to be as protective of them? Or are they going to go to the extreme and just shut them down completely? You want someone who is watching over them and setting down the guidelines. These can’t be replaced.”

It’s hard to imagine he could find an individual with his interest, drive, and resources to maintain the caves, to keep them accessible, and to protect them from damage. And what club or nonprofit would undertake the expense of maintaining caves and keeping them available when there’s no money to be made? “As I get older, I’m considering what to do with all this,” he says, as the dark river rushes by. “It’s not about the money. It’s about making sure I turn over the reins to somebody that’s going to continue the vision.”

Greg Breining is a frequent contributor to Minnesota Monthly.