|

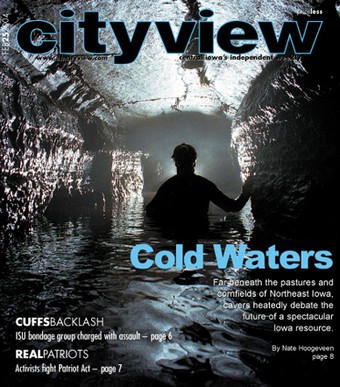

Cold Waters By

Nate Hoogeveen To download

a revised article, point your browser to: |

Coldwater Cave

may well be Iowa's wildest place. Explosions and new trenches have

some who love the cave hopping mad. One man is pushing the envelope

to answer a question: Who owns this cave?

Beneath Winneshiek County, there runs a stream. Eons ago, it likely

began as a mere trickle, exploiting cracks a nd crevices in the limestone

bedrock. Over hundreds of thousands of years, it scoured a larger and

larger pathway for itself, leaving space for air and joined by numerous

rivulets from all directions. Mineral-laden water filtered through cracks

above, dripping and flowing, depositing brilliant white calcite and

colorful substances into smooth rock formations. Over hundreds or thous

ands of years, stalactites grew down from ceilings; stalagmites up from

floors. Sometimes they met to create columns that grew microns wider

with each passing season. Other deposits flowed across walls, making

"flowstone," which undulated into myriad outlandish shapes and

sizes.

In many ways, a cave is like an ancient, living entity, constantly morphing

across a geologic timeline into something new, leaving recordings of

what it was with each layer of muddy sediment or crystalline stalactite.

But like all caves, bejeweled Coldwater Cave is not sentient. The cave

did not know or care how coveted it would become.

Iowa has seven National Natural Landmarks, and Coldwater Cave is one

of them. Among cavers, it has for decades held a mystique. Far and away

Iowa's largest cave, Coldwater has 16.5 miles of passage. It is

the longest cave in the Upper Midwest and the 33rd longest in the United

States. Festooned with formations, it is better decorated than any other

cave in the region. That, and a small river runs through it.

Despite having no actual legal protection, the cave for years has had

de facto protection from the people who owned the only usable entrance,

Kenny and Wanda Flatland. Cavers know their very presence can be a problem.

Delicate formations are easily shattered or broken off, and beautiful

caves across the country have been loved into trashiness. When cave

traffic got heavy and the trekkers tracked mud across some formations

and broke a soda straw or stalactite here and there, the Flatlands shut

cavers out for a few months to reassess. Then they worked with cavers

to get the formations cleaned, and cavers actually repaired some damaged

formations.

Last March, in a part of the cave known as the Windmill Passage, a grinding

sound filled the hall. A bit of rubble fell from the ceiling, and then

pinkish lubricant gushed from a six-inch hole in the ceiling. Time passed.

A camera emerged from the hole, right next to a clump of stalactites.

On the surface, one man was giddy. He knew this would launch the caving

community into a tizzy, and was glad of it. He had a pressing question

to answer: Whose cave was this, anyway?

*****

On a 10-degree day in December, I'm a passenger in a furniture van

heading north out of Spring Valley, Minn., toward the Minnesota Cave

Preserve (aka"The Cave Farm"). John Ackerman, a cheerful 49-year-old

Twin Cities furniture restorer with blue eyes, curly dark hair flecked

with gray and a mustache, is in the driver's seat. He owns 325 acres

- soon to be more than 500 - that at first glance appears to be typical

Midwest farmland. Examine closer, and you'll notice here and there

a grassy depression at the very center of which extends a 30-inch-diameter

pipe with a steel lid. There are 18 such structures on his property.

Each tube is equipped with an aluminum ladder. Ackerman and his caving

friends installed them to access a labyrinth of underground passages.

Some connect to one another. Others are just short caves. Each was originally

a "sinkhole," or a spot where the earth has sunk due to a gap

beneath the ground. As with many cave explorers, Ackerman's life

obsession has been to wiggle, dive and contort his way into new cave

passages - to be the first to lay fully dilated pupils on a crack in

the earth never before known by humans. Unlike others, he's made

modern excavation and demolition critical in his technique of exploration

of his cave system.

"Ever since I was a little boy, I was always interested in caves,"

Ackerman says."As you can see, it just got out of control."

He shows me one sinkhole that he's presently digging out. Aiding

him is Cave Finder, his own Caterpillar 312 Excavator, modified with

an extended boom to dig 25 feet down. There's a large pile of yellow

dirt and stones, and the gaping maw of a dirt-filled cave at the bottom

of a large hole. After the cave's mouth is dug out, he'll install

a ladder pipe, fill the dirt and rock back in, and seed grass over the

whole works.

"It doesn't look good when you're doing it," Ackerman

says."After it's done, you wouldn't know all this happened."

We drive through a field and park near a wooded area, near the main

entrance to Spring Valley Caverns. It's a reinforced concrete bunker

built into the hillside with a limestone block facade. The Minnesota

Speleological Survey keeps caving and rescue gear in it, and there's

a loft where Boy Scout groups can sleep. Open a door, and you can walk

down stairs, right into the cave. It's a nicer facility than some

state parks would have, and Ackerman built it all.

We enter the cave, where it's a balmy 48 degrees, for a nearly 3-mile

subterranean trip. Some is walkable. Other portions require crawling

on hands and knees, wading, or belly crawling (about 700 feet of it

in the"Mini-Miseries" passage), chimneying up crevices, leaping

over 70-foot deep pits, and walking with a 20-foot gorge between our

feet.

When we get past the Mini-Miseries, Ackerman becomes excitable, describing

the first time he was this far back in the cave.

"Stop. Do you hear that rumbling?"

It's almost imperceptible, but audible.

"That was a lot louder, the first time we were back here," Ackerman

says, his voice conveying the eeriness of the unknown."We didn't

know what it was, but the farther we pushed, the louder it got."

As it turned out, the quiet rumble came from the falls of a subterranean

stream in what he and Gerboth named Symphony Hall, for the multiple

tones the different cascades make. It was louder because more water

was running. When we arrive at this portion of the cave, Ackerman is

downright ebullient.

"And then we get back here and see all this," he says."It's

like a miniature Coldwater Cave!"

As adventurous as this trip is, this 5.5-mile long cave system is less

than a third as long as Iowa's Coldwater Cave. The passages are

not nearly as large. There are a few pretty formations, like the Leaning

Tower, a massive white column. But most of it is simply rocky passage

of varying shapes. There's good reason the Iowa cave is a National

Natural Landmark and this one isn't.

Spring Valley Caverns is, however, a 5.5-mile long cave system, most

of which Ackerman discovered along with his caving partner, David Gerboth.

The Big Find came in 1990, just a few months after Ackerman had purchased

his first 176 acres of the property, when there was only a half mile

of known passage in Spring Valley Caverns. Ackerman blasted wider a

long, narrow crack in which he'd noticed raccoon scratchings on

the walls.

The discovery that lay on the other side left Gerboth and Ackerman whooping

it up like high school football champs. The wider passage beyond kept

going and going. In short order, they'd discovered 5 additional

miles of cave passage. Ackerman has since added three more entrances

to Spring Valley Caverns, so you can enter one place and pop up like

a prairie dog in another.

*****

Only two people, Iowa cavers Steve Barnett and Dave Jagnow, first celebrated

the splendor of Iowa's Coldwater Cave in September 1967. They discovered

the cave by diving with scuba gear into Coldwater Spring, through about

2,000 feet of mostly submerged cave, which led to a long air-filled

cave. For the next two years, they included only one other caver, Tom

Eggert, in secret journeys to their massive find. Instead of first going

public, they went to the Iowa State Conservation Commission in 1969.

Soon thereafter, word was out. Longtime Des Moines Register outdoors

writer Otto Knauth crafted a prominent article replete with photos chronicling

the trio's exploits in Coldwater Cave. The cave captivated public

attention. The Iowa Legislature found it fit to explore the possibility

of commercializing the cave and appropriated $58,000, which culminated

in a lease agreement with dairy and crop farmer Kenny Flatland in 1971.

The state of Iowa had a 94-foot shaft drilled to make a much safer entrance

directly to the cave.

Flatland thought it was"kind of neat" that a cave ran under

his and his neighbors' property but wasn't overwhelmed. As state

scouts reported their finds, though, he became intrigued. He climbed

down into the cave with them and, for the first time, experienced the

wonderland of colorful formations, waterfalls and arching rows of tooth-like

stalactites across the ceilings.

For a number of reasons, the state deemed it infeasible to turn the

cave into a tourist attraction. It was far from interstate highways.

Many scenic areas require crawls through tight passages. Constructing

concrete walkways high above the main stream and side channels would

be cost prohibitive. Perhaps more important, the cave itself could be

a dangerous place because its water levels fluctuate by several feet.

As the name implies, no one gets anywhere without encountering very

cold water. In the wintertime, water temperatures sometimes dip into

the 30s. That makes wearing a wetsuit necessary for survival.

Whereas mountain climbers experience thin air, in Coldwater Cave, washed-in

vegetation decomposes and at times produces large amounts of carbon

dioxide, or thick air. The result is the same: hypoxia, or less oxygen

than a person is accustomed to, sometimes at hazardously low levels.

Cavers have found themselves suddenly short of breath, with headaches

or nausea, on the verge of blacking out.

The state's lease ended in 1975. Flatland had the option to have

the entrance sealed.

"I chose to leave it as it was so that other people could enjoy

the cave," Flatland says.

And enjoy it they did. Regular streams of cavers began to arrive, from

Minnesota, then Illinois, then Iowa and other states. Some of them began

calling themselves the Coldwater Cave Project (CCP). Until cavers completed

a heated shed over the entrance, Kenny and his wife, Wanda Flatland,

invited cavers into their home to change into wetsuits. Visiting with

the Flatlands in their living room became part of caving at Coldwater,

and Kenny donned a wetsuit himself to go on several epic journeys in

the cave.

Grand adventures ensued. Far back in the cave where there are only a

couple inches or less of air above flooded pools, brazen caver Mike

Nelson perfected a method of pulling his floating body along the ceiling.

"If there's enough air to get one nostril out of the water -

it doesn't need to be but an inch or so to do that - but you do

need nerve," says Patricia Kambesis, who has caved at Coldwater

since the 1970s, and now is assistant director of the Hoffman Environmental

Research Institute in Kentucky."You cannot freak out. You'll

drown in there."

Humans became like flies, scaling walls after a grappling hook was thrown

to scale a waterfall. They became worms, wiggling through muddy passages.

They became otters, swimming frigid snowmelt waters.

CCP cavers became good friends of the Flatlands, and the Flatlands were

good friends of the cave. CCP cavers showed up the third weekend of

each month, and it became expected that outside cavers would work themselves

into CCP projects, primarily involving surveying, exploring and photographing

the cave. About 15 percent of the trips were recreational. The entrance

owners relied on the living room counsel of their caver friends. The

cave became Iowa's least trammeled place - a wilderness unlike any

other in the Upper Midwest.

The CCP people published their trip reports in the newsletter of the

Iowa Grotto, the state's chapter of the National Speleological Survey.

Over the years, they became quite protective of the cave. At one point,

a rift developed between two prominent members of the group about whether

stalagmites could be removed for scientific study by University of Iowa

researchers.

One cave researcher, Calvin Alexander, a University of Minnesota geology

professor, alleges that academics began to find the cave more trouble

than it was worth throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s. They selected

caves that weren't quite the treasure trove of information that

Coldwater Cave is.

"The rules were, if you want to go in Coldwater, you suck up to

the Iowa project people," Alexander says."If you can't live

up to what their rules are, you can't go caving. I don't like

that as a scientist."

John Ackerman had never been in Coldwater Cave, but others had sung

its glories to him. His caving buddy, David Gerboth, got the two of

them invited on a Coldwater Cave survey trip after several months of

trying.

Gerboth is well known as the yin to Ackerman's yang. The two have

caved together since 1980, when they both joined the Minnesota Speleological

Survey. But it would be hard to find two men more opposite. Where Ackerman

is all guts, bravado and athleticism, Gerboth is soft-spoken, diplomatic

and not the fastest-moving caver. Where Ackerman runs a wildly successful

furniture restoration business and lives with a beautiful wife and family

in a multi-million home he constructed, Gerboth's greatest glories

for the most part happened underground.

Gerboth was quite excited to go caving with CCP surveyors. He wanted

to share with them his new map of Spring Valley Caverns, and maybe swap

ideas on mapping techniques. When they arrived and Gerboth unfurled

his map, he says he was dismissed. In the cave, the group he and Ackerman

were assigned to rushed forward. Ackerman could keep pace, but Gerboth

couldn't. Gerboth hoped to show Ackerman a particularly showy column

in the Monument Passage called the Pillar of Light Arising Out of the

Divine Reasoning. The CCP cavers wouldn't let him, even though it

was nearby, citing restorations of formations as the reason.

They did, however, let Gerboth bring Ackerman to the Windmill Passage,

where the pipe of a windmill-powered pump built in the early 20th Century

extends through the cave and downward to the water table. Driving home,

Gerboth and Ackerman simmered over their treatment in the cave. Gerboth

says that, in retrospect, maybe they should have volunteered instead

to schlep photographic gear on a less-intense photo trip. But still,

how could they treat a major cave owner that way?

Later that year, Ackerman asked Wanda Flatland if she and her husband

would sell their entrance to the cave. Nope. When Ackerman read an October

1997 issue of the Wisconsin Speleological Society newsletter, he took

great interest in an article by Gary Phelps. The editorial titled"Is

Cold Water Cave Really Open?" suggested that even prominent cavers

in the NSS received cold treatment at Coldwater.

"Whether or not this was an accurate portrayal of how things were

run there, it greatly influenced John," says Gerboth. Ackerman labeled

it a pattern, and made it his goal in life to open access to Coldwater

Cave, standing up for the little guy, wresting control from elitist

Iowa cavers.

******

Men of means typically pick hobbies or sports other than caving. Sailing

yachts. Driving golf balls. Buying rides from the Russians to the International

Space Station. In caves, mud is all about, easily slung. When John Ackerman

became fixated on Coldwater Cave, it became predetermined that the cave

would change, and that Ackerman would take heat for it. He understood

that.

Early last year, Ackerman obtained 5 acres of land surrounding the windmill

above the Windmill Passage in Coldwater Cave. Now he owns the Pillar

of Light Arising Out of the Divine Reasoning.

By March, he'd first had the exploratory hole drilled, dropped a

remote camera down the hole, saw stalactites, and rethought. He had

a larger, human-sized, 30-inch-diameter hole drilled into the cave farther

down the passage, where it wouldn't damage formations. All in all,

he spent more than $80,000 on land, drilling access to Coldwater Cave

and an easement to cave (if more cave is found to exist) on 200 acres

underground.

He announced in a post on the National Speleogical Society Web site

that he was drilling a 188-foot shaft into the cave, accusing the Flatlands

of overly tight access restrictions, and CCP members of rudeness. He

titled his somewhat warlike manifesto,"So whose cave is it, anyway?"

and ended it with,"Now who owns this cave?"

The answer still isn't clear. His announcement catapulted some of

the caving community into a tizzy. A flurry of postings on cavers'

Internet message boards decried the event as the worst thing ever to

happen to Coldwater Cave. Others applauded. All were shocked.

"In a lot of ways, it was the last little bit of true wilderness

in the Upper Midwest," laments John Lovaas, science coordinator

for the CCP,"and a rich guy has built a road into it."

Ackerman believes his entrance to be less invasive than the original

drilled entrance, partly because it is in a side passage. He takes pains

to point out that he had the drillers use the least invasive techniques

possible, at his own personal expense. Others counter that that's

fine, but a second entrance was not needed.

"He was never denied access to the cave," says Kenny Flatland."Any

caver has always been welcome. It's too bad he felt he had to spend

all that money to drill another entrance."

The new entrance wasn't the last controversy. Last month, four cavers

sniffed the acrid scent of explosives as they made their way down the

main passage. Ackerman had used a small amount of explosives to remove

large rocks near his new entrance. Ackerman says he did it because he

needed to lower the floor in order to protect stalactites that people

would have knocked off while stoop walking through the passage. He also

would eventually like to install a lift from the surface. Its platform

requires a lowered floor.

In any case, it was the first time explosives had been used in Coldwater

Cave.

Because the cave water feeds Coldwater Spring downstream, Department

of Natural Resources fisheries biologists tested the spring water for

contaminants."Live fish were observed in the spring run," read

the report. "Caddis fly cases were abundant on the rocks also. Nothing

was observed out of the ordinary." The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

has said it has no jurisdiction to require permits for activities in

Coldwater Cave. Essentially, caves in Iowa are a sort of legal no-man's

land, with no applicable legislation or case law established.

"Every state that has caves should have a cave protection act,"

says Lovaas."They are unique ecosystems. They are a very alien landscape

that's very fragile. Whether most cave protection acts would affect

what Ackerman is doing, I don't know."

One caver in the group, Dawn Ryan, was particularly incensed that Ackerman

had modified the passage. He had threatened via e-mail in August that

he would do exactly what he did if she didn't stop publicly criticizing

him. She says she stopped.

"When I saw this, I was really surprised that he lied," Ryan

says."I understand what he's doing is perfectly legal, but does

that make it right?"

More recently, Ackerman has threatened that if the criticism - or "publicly

destroying my integrity" - doesn't stop, he will string an electric

fence across his property line in the cave, effectively cutting the

cave in half. First, though, he says he would discuss it with the Flatlands.

"You know [putting up the fence] won't happen," Ackerman

says. "The Flatlands will probably intervene with these people."

Lovaas is surprised that for all the arrows Ackerman has lobbed over

the CCP's elitism and the Flatlands' alleged access restrictions,

he can't seem to handle criticism." Dawn comments on the landscaping

in his passage, and he accuses her of slander. "It's like having

a nutty neighbor."

Ackerman's friends say he's just often misread. Alexander, the

Minnesota professor, says he finds Ackerman's confidence inspiring."

What come off as statements of incredible bravado are really simple

statements of what he is doing, has done or plans to do. He's not

bragging. Sometimes he does threaten people."

Having spent time with him, it is difficult for me to reconcile the

Ackerman of blustery digital pronouncements with the personally pleasant

and jovial Ackerman who's fun to cave with - even if he does have

the tendency to get carried away with grand schemes that outsiders are

hard-pressed to understand. Is John Ackerman a raging cave monster,

or is he the most exciting thing ever to happen to Midwest caving? Ultimately,

it's a question that will be answered only by his actions, not by

what is said about him now.

Of course, CCP cavers get carried away with rhetoric, too. It all stems

from passion about one spectacular cave.

A good number of Coldwater Cave Project cavers have simply accepted

Ackerman's presence in the cave, modifications and all. Although

she doesn't believe Ackerman's access was necessary, Kambesis,

who's caved on high-profile exploratory trips in the country's

longest caves, points out that Ackerman is certainly within his rights.

She does wish Ackerman's announcement were less confrontational.

She also figures Ackerman could have tried harder to work with the Flatlands

to cave from their entrance.

"Cavers modify caves all the time," she says."Most major

discoveries have resulted from some kind of modification to get into

them. We'd be hypocritical to say this new entrance is evil"

*****

Ackerman brought me to his Spring Valley Caverns because he wants me

to understand that, while he's taken cave modification to a new

level, he's also constructed his very own conservation ethic. After

he blasts, rubble is piled in low spots, covered in mud. From a purely

aesthetic point of view, Ackerman is correct. His cave, once you're

inside it, appears very natural. For future generations, he believes,

cavers will still cave here, giving nary a thought to the modifications.

The caves he has exposed and protected within his Minnesota Cave Preserve

will be his legacy, perhaps held in a trust, run by a conservation organization

or by state government.

After we emerged from a pipe at Spring Valley Caverns, John Ackerman

and I drove across the border into Iowa. Ackerman unlocked the lid on

a tube. We begin climbing 188 feet down. Rung after rung, the circular

patch of gray sky gradually became a dim star above. As the shaft angled

slightly, it disappeared altogether.

We only spend a half hour in Coldwater Cave, but it lived up to its

billing. The Pillar of Light is indeed glorious. An impressive waterfall

dumps into the main stream a short hike from Ackerman's entrance.

Formations are everywhere.

Ackerman appeared infatuated."This cave makes mine (Spring Valley

Caverns) look like a gopher hole," he said. He wanted me to see

this, to feel the excitement, and I did. I know why he wanted in here

so badly.

*****

So what's really changed at Coldwater Cave?

Ackerman says no one's beaten down his door to use his entrance

into the cave. Two months later, a month after the blasting, I asked

Ackerman about his intentions. Because Coldwater Cave is part of his

Minnesota Cave Preserve, he plans for his portion to have the same protective

status he hopes Spring Valley Caverns will one day. Both will have liberal

access for cavers.

Would Ackerman use explosives to open new passages? He said he'd

have to come across a situation before knowing that, but pointed out

that CCP cavers had used everything short of blasting - shovels, sledgehammers,

electric drills, and so on - to open new passages.

Ackerman has a motto to "break bones, not formations" in his

caves. He's drilled new entrances simply to protect sensitive areas.

If a formation is in the way of exploration, the decision to proceed

is discussed at length. Alexander has a unique double stalagmite in

his University of Minnesota laboratory that Ackerman carefully photographed

and then removed because it was blocking a new passage.

At the same time, Ackerman does extend olive branches."I told Kenny

- and there are witnesses - that I would weld my access lid shut tomorrow

morning if you open your cave to scientists and to responsible cavers

who you approve' The offer is still there."

The answer to Ackerman's pressing question - Who owns the cave?

- has become murky with the talk of fences. His point in asking the

question while drilling a new entrance was that ownership was really

about control of access. Legally, one owns the same amount of land in

the cave that's surveyed on the surface. Ackerman has demonstrated

that one can also purchase caving easements to areas one doesn't

own outright.

But perhaps such a resource should be viewed as"owned" by everyone.

Perhaps that's why many large caves outside Iowa have become protected

as national or state parks, and while access isn't perfect, many

are happy just to know certain places are protected.

Ackerman is not to be ignored, and his presence at Coldwater Cave will

likely continue to generate questions never before asked.

"This is kind of the Wild West of our time," says Iowa Department

of Natural Resources ecologist John Pearson. "Can someone put up

a fence in a cave? It's going to be up to Marshal

Dillon and Judge Roy Bean to sort this out."

To

download an updated article about the Cold Water Cave project, point your

browser to:

http://www.karstpreserve.com/ColdWaters.pdf